Knackered. That is how I would describe what I felt after three hours in the saddle on my last motorcycle trip in the Himalayas 16 years ago.

Honestly, the 1998 Royal Enfield Machismo is not the most comfortable motorcycle for the broken roads of Ladakh. It looks all very exciting in the photos, but the rudimentary suspension and the non-pliant iron chassis results in a feeling of numbness below the belt. Hence ‘knackered!’

In the subsequent years, when driving in the high Himalayas, I would come across motorcyclists on thumping Royal Enfields and shake my head in pity at what the poor chaps were subjecting themselves to, and I would mutter, “Never again,” to myself .

But when it comes to the Himalayas, you can never say ‘Never again’. So when I got a call from Royal Enfield inviting me for a ride, I was already racking up excuses to politely turn it down as the person on the other end went through pleasantries. But then, she said, “Everest base camp in Tibet”, and, two months later, I was sitting with a bunch of Royal Enfield-afflicted rogues in the garden of the Hotel Manaslu in Kathmandu.

First of all, let me give you a quick geography and history lesson. Mount Everest straddles the border of Nepal and the Tibet Autonomous Region (China). So there’s the south base camp that is in Nepal and the one people trek to.

The Everest base camp in Tibet is at the base of the north face – from where George Mallory and Andrew Irvine climbed Mount Everest in 1924 and tragically, never come down again. Before their ascent, they stayed at the Rongbuk Monastery at the base of Everest, and it is there that we were going to ride to.

Our merry bandwagon consisted of 11 riders, of which four, including me, were from the automobile media fraternity. Then there was a lead and a sweep, two enthusiasts, two Royal Enfield content crew members, and a local guide from Nepal.

It was in Kathmandu that I first swung a leg over the Royal Enfield Himalayan, before we made our way towards Batar, 70km to the north. To say that the Himalayan surprised me would be putting it lightly. It was the most non-Enfield-like Royal Enfield I had ever ridden. It is said that a Royal Enfield is built like a gun. Well, my Machismo feels like a handmade gun from a questionable part of Uttar Pradesh, whereas the Himalayan feels like one off the line of a leading arms manufacturer. First of all, the Himalayan has negligible vibrations; hence, there is just a single image in the rear-view mirror, and wonder of wonders, there are no false neutrals.

Sabin, our guide with far-sighted wisdom had led us towards Batar on a route that was a shortcut to avoid the holiday traffic on the main highway. Nepal’s creased and crumpled topography, along with its minuscule road repair budget and the recent monsoons, meant that this route was rampant with slush and mud. Long sections of narrow road wrapped around hillsides were no more than deep ruts of slippery and slimy slush. And it is here that the Himalayan showed me the kind of confidence it doles out. I have very little experience riding off tarmac and I don’t really enjoy it, but the Himalayan, with its knobby Ceat rubber and tractor-like torque at 1,500rpm in the first gear, just piles on assurance. Point the bike towards the best line through the muck and slush, keep the throttle steady and stay off the clutch, and it will power through like a determined donkey.

On those two days through Nepal, towards the China border, I unwittingly hammered the bike because there were so many technical off-road sections along the route. But not once was any jarring shock transmitted to me; the front fork with its seemingly forever 210mm of travel and the compliant rear monoshock swallowed and buffered everything. Besides that, the ABS was a real comforting factor – especially on these roads where the coefficient of friction was fickle; as was the assorted traffic of pigs and livestock.

During these two days, our route was through Nepal’s humid Terai with temperatures touching 30deg C and the going was hot and sweaty. But the morning we started off from Dhunche towards the border at Rasuwa Gadhi, there was a definite nip in the air. It was a sign of things to come.

We had to leave by 7am because, across the border, Tibet follows Beijing time, which meant it was two hours ahead. And, Sabin was already getting panic calls from Tenzing, the guide who would lead us in Tibet. He was worried that if there was a crowd of other travellers at the border, we might get delayed and then the officials would break for lunch. But it was all for naught. We were stamped out of Nepal and into China within 45min.

In that time, we had to carry our luggage across security and immigration where every piece was scanned and some physically checked. Every phone was scrolled through. Any anti-Chinese or pro ‘Free Tibet’ propaganda on your phone can potentially get you debarred from entering China. Sabin had warned us of this and every phone had been ‘sterilised’, so to speak, the night before.

After the luggage had been taken across, we walked back to the Nepal side to wheel the bikes across as custom officials verified the chassis numbers with those mentioned on the permit.

The 24km ride from the border to Kyirong was an absolute delight. In that distance, we gained 2,000m and the switchbacks were a motorcyclist’s delight. Perfectly cambered and well-marked and sticky tarmac meant that we could delightfully dive into corners for the first time since we started from Kathmandu. But we had to remember to ride on the right because China, like Europe and America, drives on the wrong side of the road.

The difference across the border is stark. Nepal just 25km to the south was definitely rural with broken roads and haphazard constructions. Kyirong, on the other hand, was well-laid-out with symmetry, signal lights, supermarkets and stylish restaurants.

The only thing Tibetan here was the language. Otherwise, going by the food and the flags, this was for all practical purposes China. It was regarding this that Tenzing gave us a very sombre briefing the next morning before we started to ride.

“Phrases like ‘Free Tibet’ or ‘Long live the Dalai Lama’ could easily get you into trouble and I will not be able to do anything about it,” he emphasised in a tone that was mildly threatening.

He went on to warn us against unfurling any sort of banners for photos or wearing any T-shirts with Tibetan motifs or prayer flags. In short, what he was saying is that you need to behave as if Tibet didn’t exist.

On that day we rode 270km to Tingri and gained 2,000m in altitude. I remember smiling when I was riding on the baby-bottom-smooth black tarmac of the Friendship Highway that runs across the Tibetan Plateau. As I crested the 5,100m-high Tong La mountain pass, the Shishapangma came into view – the first of the eight-thousanders at 8,027m high.

While it was really cold (-2deg C with wind chill), this time of the year was gorgeous when it comes to the view. The sky was a deep blue and the snow-capped peaks shone in the bright sun. Soon the blue of the sky paled in comparison when Lake Paiku (at 4,591m) came into view.

Our altitude gain had been rapid and soon acute mountain sickness started to raise its ugly head, as assorted headaches and nausea broke out in the group. But the very first sight of Mount Everest, 35km short of Tingri, assuaged some of it.

At Tingri, Tenzin and Sabin went around with an oximeter to gauge everyone’s health. My oxygen saturation reading at 65 was alarming because everybody else was at 85-91, and I was told that I might have to stay back in Tingri. But I took it easy that night, drank more water than Lawrence of Arabia’s camel, and I was bright and shiny by the next morning. Two chaps, however, did have to stay back in Tingri.

That 140km route from Tingri to Rongbuk Monastery was simply the best ride of my life. Everest, Lhotse, Makalu, Cho Oyu, and Shishapangma were constant companions. I was truly riding on ‘the roof of the world’, as Tibet is called.

And when I stood beside my trusty, mud-splattered motorcycle on the 17,100ft-high Kya Wu Lha Pass, it struck me that I was at an altitude higher than what I had skydived from – 15,000 ft!

The view from the pass sent a palpable excitement through me, because not only does the shiny Everest beckon like a beacon, but the road down the pass consists of 108 switchbacks of smooth, unblemished tarmac. It is the only time I wished I had a motorcycle with quicker acceleration and closely packed gear ratios, unlike the tall ones on the Himalayan.

However, it is on this road with Everest as a constant companion that clarity shines through regarding what it’s about motorcycling that zen is often associated with it.

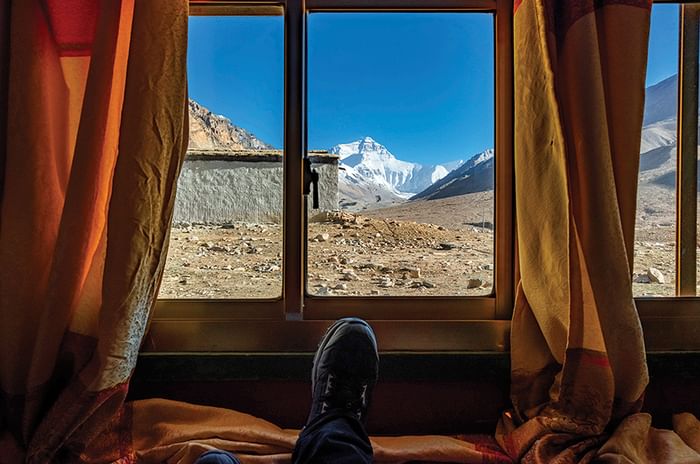

When we got to Rongbuk I was in awe. I had expected to see Everest, but not like this – so close and towering over the little monastery. The base camp hotel here is very basic, though they do have electric blankets and that is a boon. But the toilets are rudimentary and lacking any kind of privacy. If you want to go you will just have to strut your stuff.

But throwing my curtains open the next morning and seeing the Mount Everest framed in my room’s windows made me realise that exhibitionist loos were a small price to pay.

I opened a window and climbed out into the sub-zero cold, dressed only in shorts and a T-shirt. But I didn’t care because it was Mount Everest! And as George Mallory said all those years ago, “It is there”, and it’s right in front my face, and I couldn’t be happier!

RISHAD SAM MEHTA